|

1995

Rally IV – The “Turboville!” Rally

|

|

|

-kw.jpg)

When:

June 16-18, 1995

Where: Central, Pennsylvania

TURBOVILLE!

by

John Burns

Motorcyclist

Magazine November 1995

"The

turbocharger is an ingenious little scavenger of a device, living off

the poisonous fruits of internal combustion and producing from those

noxious fumes something beautiful and uplifting - Horsepower. During

the belle epoque of the early 1980s, turbocharged motorcycles were

all the rage. Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha each built one, while Honda

produced two. The premise was simple in concept - liter-class power

from a mid-displacement engine. The practice was slightly more

complicated, unfortunately, and the turbocharged motorcycle went away

with much less fanfare than that which had greeted its arrival.

Still, the turbo retains its adherents. Holed up in remote mountains

for the most part, living in caves, gathering parts by day and

swapping stories of awesome, mirror-flapping, fifth-gear wheelies

around the campfire by night, the Turbo Motorcycle International

Owners Association sees its mission as keeping those tiny impeller

blades spinning until such time as the Great Pumpkin rises gloriously

from the grave, makes big power and puts the motorcycling world back

upon the true path to high performance.

At the

gracious invitation of T.M.I.O.A. president Bob Miller, we

attended the club's rally in beautiful Central, Pennsylvania, in June

of this year. Though the T.M.I.O.A. boasts an international

membership numbering in the hundreds, the hardy and somewhat motley

band that assembled in Pennsylvania numbered, oh, about 15 - one

Honda CX500T, a handful of well-kept CX650Ts, a few Kawasaki GPz750

Turbos, two Yamaha 650 Turbo Secas and one (drum roll here) Suzuki

XN85, the rarest and most precious of the turbo bikes. (We always

wondered why Ienatsch was holding on to that old Suzuki Turbo so

tightly).

They also let a few guys in on CBXs

and that type of thing just for fun. Rally headquarters, the Park

Central Hotel had been booked up by the time we made our plans (the

day before the rally), Fishing Creek Lodge and Bakery. Dolly runs the

place and is famous for her sticky buns.

The

real HQ (far as I was concerned anyway) was the Park Central's bar.

Central, Pennsylvania, is not only not on a freeway (or turnpike),

it's not even on any kind of two-lane. You turn off a remote two-lane

onto a little blacktop road (if you see the sign) and travel back a

few miles and maybe 50 years to get there. There's a little store,

the hotel, Dolly's sticky buns, a few houses and a lot of trees.

That's it

The hunting lodge-like Park Central

has every known species of mammal (including a buffalo) stuffed and

on display, and they all peer over your shoulder from the walls and

ceilngs while you eat as if they'd like a bite if you could spare it.

Somebody recently shot an 853- pound black bear nearby, Bob Miller

reports. People at the bar are incredulous that you were able to

actually find them from Los Angeles. What's the deal with O.J.?, they

want to know. When did you last speak with him? How did he seem?

Valley Boy Wing nearly foundered on steamed clams when he saw they

were $8 a dozen. Here it was, then in search of the elusive turbos,

we had stumbled into God's country. 'Twas Honda that got the ball

rolling in 1982 with the world's first production turbocharged

motorcycle, the CX500TC, which was based upon the lowly CX500

transverse Vtwin.

Boasting not one but two

(count 'em) computers ,one to deal with ignition timing and another

for its fuel injection, the CX-TC slid down Honda's skids at a time

when things now as mundane as liquid cooling and

four-valves-per-cylinder were just beginning to make headway. The

Turbo seemed to point the way toward a glorious, high-tech future. In

truth, the bike was more mechanical nightmare than beautiful dream,

with more hoses and wires than the Red October.

Also, turbochargers don't do much for the engine they're attached to

until spinning up under load. For around-town, low-rpm use, the Honda

was not quite as hot as its spec sheet insisted. All that fine

trickery and futuristic plastic added up to a 575-pound (fully

gassed), top-heavyish motorcycle being pushed around by a 497cc twin

with a compression ratio of only 7.2:1.

And

then there was lag. The Honda Turbo suffers from a large dose of it.

Lag lets you know you're riding some thing special, a turbo!, and too

much of it makes clear why turbos stopped being produced. By the time

the power you ordered gets to the table, you've often lost your

appetite (on a road with curves, at least).

Later in '82 came Yamaha's entry the XJ650LJ Turbo Seca. While Honda

saw its turbo as a technological communique to the world, Yamaha took

a far simpler, though barely cheaper, approach: Instead of fuel

injection, the Seca Turbo used a bank of 30mm CV Mikuni carburetors.

A tiny, Mitsubishi turbo unit with an exhaust impeller 39mm in

diameter was tucked away beneath the swingarm pivot, where exhaust

impulses from a normal-looking set of header pipes kept it whirring

away at around 170,000 rpm. A big tube then fed pressurized, filtered

air from the turbo up to a sealed airbox - your basic

blow-through system. Naturally, it's not quite that simple. Fuel,

too, must be pressurized to keep turbo boost from pushing it back out

of the float bowls and into the fuel tank, so a fuel pump and

regulator system was devised to maintain fuel line pressure just

above boost pressure. Also, special jet needles, tapered sharply at

the end, allow the Seca Turbo's carbs to deal with the super-dense

air being rammed through at maximum boost without leaning out the

mixture too far and causing a nasty explosion.

It basically all works as advertised in the Seca. There's less lag

present than with the Honda mainly because Yamaha began with a bigger

engine, and, since the Seca doesn't build as much boost as the Honda,

Yamaha didn't need to drop compression as much. Therefore, the

transition from off-boost to on is less abrupt.

The Seca feels like your average early '80s-era air-cooled UJM until

about 6000 rpm, whereupon the sensation is that of an invisible hand

reaching down and scooting the bike airily along. The Seca feels very

unstressed and quiet cruising along at 70 or 80 mph. (A turbocharger

makes a pretty effective muffler. The turbo club must be one of the

quietest internal combustion groups around).

Other Seca components are less endearing than its mill. Air-assisted

suspension was a big deal at the time, too, but we don't know why.

Not to mention single-piston brake calipers scary enough that the

deer know to stay off the road when they see a Turbo Seca coming.

Skinny tube frame, 36mm fork tubes, bouncy shocks, shaft drive, crap

brakes and big power combine to make the Seca our candidate for Most

Likely to Hurt Somebody.

It's a weight thing.

That tiny turbo wound up making the Seca Turbo 65 pounds portlier

than a regular 650 Seca. At 567 pounds it's just about the same as

Kawasaki's hot-rod GPz1100 and quite a few pounds more than the

Suzuki GS1100E, both of which could smoke the Seca like a cheap

cigar, and out-handle it, too.

Suzuki fired its

turbo gun in late '82, and the XN85 bobbed immediately to the surface

as the best turbocharged bike available. Similar to the Yamaha in

layout, Suzuki tucked its IHI turbo behind the cylinder block of an

air cooled in-line four, driving it through a normal-looking exhaust

collector. Like the Honda, it relied on electronic fuel injection for

mixture control; in Suzuki's case, a gate-type flow meter measures

incoming air, which is sucked through the turbo and shoved into the

engine, with the proper amount of fuel injected just before entering

the head. Very straightforward, if not particularly powerful.

The XN feels the least turbo-y, so seamlessly does it come on boost.

To make up for that, it has the trickest Buck Roger's liquid- crystal

boost gauge to inform you of all the electro mechanical trickery

taking place below. All the other bikes have LCD boost displays, too,

but Suzuki gets the MBA (Mario Bros. Award). (Wonder what ever

happened to the motorcycle industry's fascination with the LCD? The

best part of my old 750 Seca was the instrument panel).

Anyway, it was really the XN's handling prowess than won the hearts

and behinds of the canyon-addled Californian bike press, not so much

its motor. Not only did the Suzuki weigh some 25 pounds less than the

Honda and Yamaha, it was the first production turbocharged bike with

a 16-inch front wheel (ooh, ahh) and the first street-going Suzuki to

get a Full Floater (i.e., single shock) rear end. It would go happily

around corners, basically, where the other turbo bikes seemed

reluctant. What defines the Suzuki now is its rarity. The Turbo

Association thinks only 300 were built, and only about 130 of those

were titled in the United States. How many are left? To turbo guys,

the XN is the Holy Grail.

Second-rarest would

be the Honda CX650T, of which just over 1100 came Stateside. Launched

mid-1983 to the probably considerable consternation of those who'd

just bought CX500Ts, the 650 was a vastly superior product -

177cc more displacement and a higher compression ratio went a long

way toward curing its off-boost ills, bigger valves and a bigger

turbine gave more boost, and the two computer functions from the 500

were taken over by but one black box in the simplified 650.

A little saddle time on a 650 Turbo reveals what all the hoopla was

about. Once the tachometer gets to about 2500 on the Honda, a little

more throttle rotation sends it into full Star Wars mode. Sounding

like a muted Ducati, the 650T does a sort of big-dog-wagging-its-tail

shudder before launching itself down the road with the progressively

faster feel of being attached to a giant bungee cord. Absolute top

end is no great shakes, but mid-range power is amazingly good, even

by current standards. Boost, you realize, is a good thing,

particularly when it's attached to an engine that sounds like a stock

car. The 650T's hellacious mid-range made it the roll-on champion in

'83, thrashing even the mighty Suzuki GS1100 from 60 mph. Also, the

Honda's chassis feels as solid as, say, that of a new ST1100 Honda.

There's a little movement, but overall the bike's suspension is

nicely buttoned down and controlled. Some people collect bikes that

make you wonder what their parents did to them. Not so the Honda

CX650T. It's still a fantastic sport-touring motorcycle.

Last and by all means beast came Kawasaki's ZX750 Turbo. Based upon

the GPz750 platform, Kawasaki engineers decided to largely eliminate

lag by placing the turbocharger as close to the exhaust ports as

possible. To that end, the ZX mounted its 47mm compressor in front of

the engine, and squeezed all four head pipes into it about eight

inches downstream from the head. Clean air came via a tube routed

beneath the left side of the bike's KZ650 cases, through an oiled

foam filter mounted outboard the counter-shaft sprocket. Post-turbo,

another steel tube ran the pressurized air back to a plenum in the

normal in-line-four location, where it met up with a Digital Fuel

lnjection system similar to that found on the GPz1100.

Strapped solidly to Kerker's Schenck dynamometer, the Kawasaki

bellowed out 94.6 horsepower for Cycle magazine's November 1983

issue. That would equate to around 100 Dynojet horses (the Dynojet

being the typical, rear-wheel-measuring dyno commonly in use

today).

For its day, then, the Kawasaki was an

absolute animal, able to burn through the quarter-mile a half-second

quicker than its nearest rival and with 10 more mph through the

lights. Motorcyclist's test bike clocked 10.99 seconds at 123.2 mph.

Now that a decade has passed, those numbers are achievable by

normally aspirated 750s, but all those bikes weigh a lot less and

launch themselves from much meatier rear tires. Curious, isn't

it?

On the road, the Kawasaki's 12-year old

engine still pulls hard, particularly from about 6000 rpm. Dialing in

a bit more throttle from there, in any gear, provides whooshy,

silent, near liter bike thrust with almost indiscernible lag. There

you are, cruising along at what feels like 65 mph, only to glance at

the speedo which reads...85. The Kawasaki carries steep gears and

blows through them effortlessly.

Why did the

turbo go away? Cost, naturally, figures heavily, and complexity adds

cost both for manufacturer and buyer. Also, the early '80s were a

tough time for the Japanese, who found themselves with too many

unsold bikes gathering dust in warehouses, as well as a hostile U.S.

administration which shortly thereafter saw fit to slap tariffs on

imported bikes over 750cc (which really should've been a good thing

for turbo production). Anyway, the Japanese suddenly perceived the

need to economize, and turbo bike sales had never exactly boomed.

Custom cruisers seemed to be the coming thing.

Riding any of these bikes makes you wonder, though, what might have

been? None are great twisty-road mounts (nor were most of their

non-blown contemporaries), but for sport touring duty, they (their

engines, at least) are all excellent, producing steaming platters of

always usable middle-rpm power and torque that would yank Wilma right

off the back on the way to Americade.

A

turbocharged Honda ST1100 or Gold Wing could be truly interesting,

and on a bike that already weighs six or 800 pounds, why not? The

automobile phylum certainly hasn't given up on turbos: Look no

further than Porsche's wildly powerful new 911 Turbo, possibly the

hottest four wheel vehicle on the planet.

In

the meantime, the Turbo Motorcycle International Owners Association

wants you, and you should want them if you own or have any interest

in turbo bikes. The Association's quarterly newsletter will make your

journey to pressurized Nirvana easier. Not only was the living easy

and the meals a deal at the T.M.l.O.A.'s last rally in Pennsylvania,

you could still get Hole on the radio. WHOOOOOOSH! Turboville!"

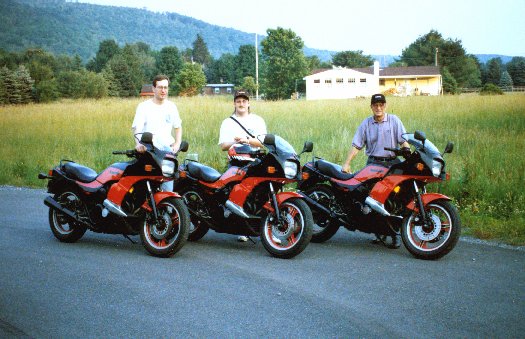

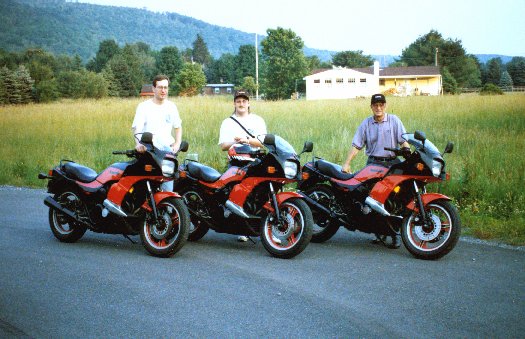

Modern

Day Musketeers in Central, PA

(Turbo News Editor Steve Klose,

Ennio Alexandro, and Glen Edwards)

Home

About/Contact

Us Bikes

Rallies

Tech Help

Merchandise

Classifieds

Newsletters

Turbo People

Photos

Forum Links

Disclaimer

© Turbo Motorcycle International Owners

Association

-kw.jpg)